Tug Of War - A Sport for the Modern Olympics

Introduction

This page celebrates the sport of tug of war, a sport so often regarded as little more than a quaint and friendly tussle in a field for the entertainment of visitors to a village fete. And yet tug of war has a very long history and a worldwide history, and it is - or it can be - a genuinely serious test of many athletic virtues. And what's more, tug of war was once a bona fide Olympic sport.

In the opinion of the author of this article, tug of war should once again grace the Olympic stage, perhaps in new and engaging forms. Tug of war is, as this article argues in words and photos and videos, one of the purest of all Olympic sports.

N.B: Please note, all my articles are best read on desktops and laptops

The History of Tug of War

It is not possible to give a date for the origins of the tug of war - the whole premise of this article is that this is one of the most natural manners in which athletic ability can be displayed. As such, it could perhaps be frivolously dated back to when the first caveman and the second caveman had a big dispute over a mammoth carcass and each grabbed one end of a leg and tried to drag it off to their respective dwellings. You take the point - using strength to pull or drag has always been a very natural part of life, and the only question concerns the date when this action was turned into a sporting contest.

As long ago as 2500 BC, evidence of a form of tug of war contest was being recorded on wall engravings in a tomb in ancient Egypt. This can be seen in one of the images on this page. No ropes were used, yet two groups of men are pulling against each other in what appears to be a stylised trial of strength (1).

In ancient Greece c 500 BC, tug of war may have been a sport in its own right, but was certainly also a training exercise for other sports, testing as it did, the prized virtues of strength, stamina and discipline (1)(2)(3)(4).

And in China, there is a Tang Dynasty description of tug of war as a training technique for warriors in the State of Chu. Emperor Xuanzong later sanctioned games in which ropes of more than 150m (500 ft) in length were pulled by teams of 500 or more men. Drummers would give rhythmic accompaniment to the tussle (5).

By the 11th century AD, we have records from Northern and Western Europe. In Scandinavia the Vikings indulged in various pulling trials of strength. One was a contest in which teams reputedly competed to pull heavy animal skins over pits of fire (1)(5). Rather less violent (and perhaps a little less Viking-like) was a contest in which two men may have sat facing each other with their feet together. Grabbing the ends of a short rope, they would have tried to pull each other over (6). Today, some Canadian eskimos have a similar contest known as 'arsaaraq' (2)(4).

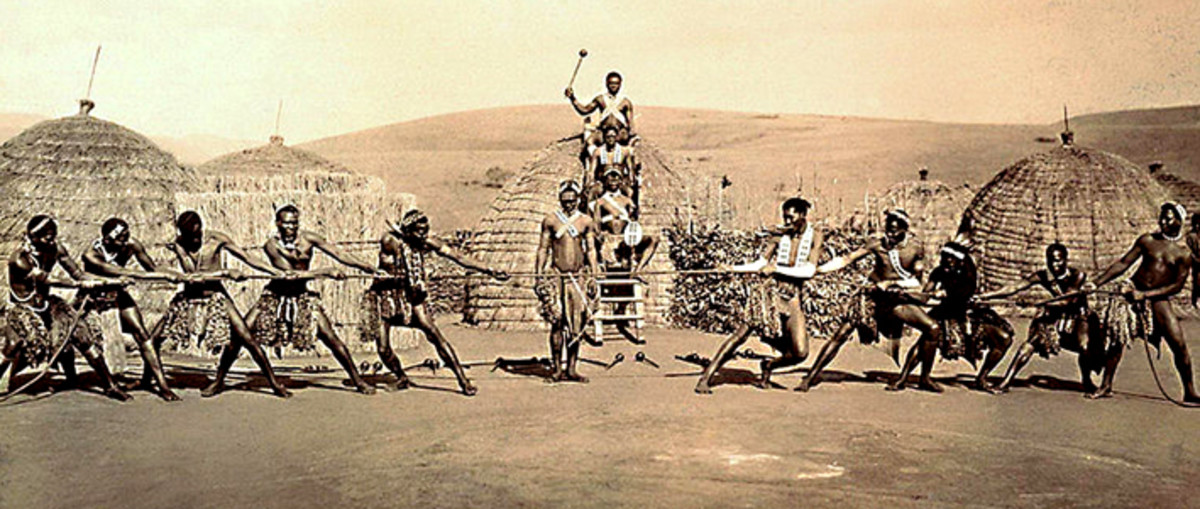

Since the 11th century, records of tug of war in all its forms - with or without ropes, in single man or team competition - have surfaced across the world, either from eye witness accounts or from depictions in works of art. In Afghanistan a wooden pole was used instead of ropes. And in 13th century India, tug-of-war was depicted on the Sun Temple of Konark in the State of Orissa. In the 16th century, contests were held in England and France, hosted by the gentry in their castles and mansions. Other records come from as far afield as Burma and Hawaii, Mongolia, Turkey, Korea and New Zealand (1)(2)(4). It seems whether for fun or exercise, or as part of an elaborate ritual, this sport was really developing a world-wide appeal.

19th Century Tug of War - The Sailing Ship Connection

Although practised across the world in past centuries in some form or other, tug of war clearly could not have been described as coordinated. There were no rules, no organisation and no international competition. It does seem that these next important stages in the sport's development were brought about indirectly by the emergence of the British Empire. The only way to establish a global empire was through ocean travel on war ships, trading ships and ships of exploration, and as Britain became the dominant sea-faring nation of the 18th and 19th centuries, so tug of war became something of a sea-faring tradition. This was not really very surprising, because the hauling of ropes was an essential part of the life of crews before the age of steam. Raising the sails, adjusting their position relative to the wind, and securing the ship in port all involved tough rope pulling and disciplined team work. And there is a strong suggestion that this is where the modern sport of tug of war truly has its origins. In the last days of sailing ship domination in 1889, the sport was observed on board the famous tea clipper, 'Cutty Sark', when it was docked in Sydney Harbour, Australia. The crew were seen to be engaged in a 'pull', and the Bosun explained to an army officer who watched the event that the friendly rivalry and exercise helped ensure the fitness of the men for the long sea voyages they had to undertake in those times (1).

Indeed, sailing ships may well have given us not just the form of the modern sport, but also its name. Dictionary researches give two meanings for tug of war. One, of course, is the sport we are describing here. The other however, is a generalised term for any struggle for supremacy between two opposing forces. And according to the Oxford English Dictionary, this may have been the original meaning of the phrase. The term 'Tug of War' or 'Tug o' War' as it has been known, was first applied to the age-old sport only in the 19th century, possibly even as a corruption of 'Man o' War' - the name used for the sailing ships of the Royal Navy (1)(5).

With Empire, the sport spread even further, and was recorded as being popular in India among army units (1)(2)(5). And with the return of army and navy personnel to their homes in Britain, so tug of war was introduced to the wider community and to all levels of society. Whatever the reasons, it seems to have been approaching the peak of its popularity as a true sport towards the end of the 19th century. Competitions were organised, clubs were formed and the first official rules were laid down (1).

Olympic Representation

The rapid development of tug of war in the late 19th century coincided with the reinstatement of the greatest sporting festival of all. The modern Olympics were first staged in the year 1896, and very soon after this, tug of war came to the attention of the Olympic Committee looking for sports to feature.

1900. At the Paris Olympics in 1900, it happened. Tug of war became one of twenty sporting disciplines held that year. Three teams entered, but the United States team had to withdraw because of a scheduling conflict (three of their contestants were also competing in the hammer). Thus the only match was the final. A joint Swedish and Danish team of six men defeated a French side. That first Olympic event would also claim two other historic firsts. The Scandinavian triumph gave Sweden their first ever Gold Medal*. And the participation of a black puller in the French team resulted in the first ever medal for a black athlete. (That same athlete - a Haitian born French puller called Constantin Henriquez de Zubiera - later became the first black sportsman to win Gold*, when he competed in the rugby union event) (2)(7).

1904. Between 1900 and 1920, tug of war was an official Olympic sport, and it began to blossom. In 1904, six teams from three nations took part, but the host nation - the USA - took all the honours, with the Milwaukee Athletic Club winning Gold (2)(7).

1908. Great Britain emulated the U.S clean sweep of 1904 in the London Games of 1908, with the City of London Police taking Gold. By now the number of pullers per team had risen to eight (2)(7).

1912. In the next Games in Stockholm, the host nation again won the Olympic title with Sweden defeating Great Britain (2)(7).

1920. After a brief interlude (necessitated by the First World War) tug of war again returned to the Olympics in 1920. Great Britain won the Gold, the Netherlands took Silver, and Belgium took the Bronze (2)(7)

And that was it. After the 1920 Games, it was felt the number of competitors at the Olympics were too many to manage, and competition was trimmed from 156 to 126 medal winning events. Tug of war was one of the casualties. It never returned.

*To be strictly accurate, most of the winners in 1900 received cups or other trophies. To ensure early athletes were all accorded their proper place in Olympic history, the awards were later upgraded by the International Olympic Committee to Gold, Silver and Bronze medals for the first three placed competitors (8).

The Worldwide Appeal Which Breaks All Barriers

Official Organisation of Tug of War Since the Olympics

During its Olympic hey-day, tug of war was always contested as a part of the track and field athletics programme. In the aftermath of its rejection by the governing body, it now had to make its own way as an independent sport. Funding had been lost and organised international competition was gone. There can be no doubt that tug of war suffered after it had been dropped from the Olympic programme, but enthusiasts were determined to keep the sport alive in whatever ways they could (1).

Their solution was to develop autonomous associations and then eventually to unite these into a world governing authority. And that is what happened over a period of decades, spearheaded by the old Olympic powerhouses of the sport. The first national association to be formed was in Sweden in 1933. In 1958, England formed the Tug of War Association (ToWA) and the Dutch followed suit in 1959 (1)(2)(4).

Then in 1960, several of these nations came together and formed the Tug of War International Federation (TWIF) under George Hutton of Great Britain and Rudolf Ullmark of Sweden. Soon after this new governing body first met, an International tournament was organised, with teams from Sweden, Denmark, the Netherlands and the UK participating in the 1964 Baltic Games in Malmo. One year later in 1965, the TWIF held its first European Championships at Crystal Palace in London. And when nations from outside of Europe began to join the Federation, the next logical step was to instigate a World event, and this happened when the first ever World Championships was held in the Netherlands in 1975 (1)(2)(4)(9).

In 1978, an important boost was received with the first appearance of an American team in the World Championships under the auspices of the newly formed United States Amateur Tug Of War Association (USATOWA). In America today, the sport is strongest in the upper Midwestern states of Wisconsin, Minnesota, Illinois and Iowa (1). Many new national authorities were now being established, including the Scottish Tug of War Association which was founded in 1980 - as a result, tug of war became a regular feature of the famous Highland Games (5).

Also in the year 1980, but quite independently of all these other advances, a new organisation - the International World Games Association - was created with the specific intent to promote a range of sports which are excluded from the Olympic games. This would be good news for tug of war, as the sport was given the backing of the new group and included in the first 'World Games' event which was held in Santa Clara in the USA in 1981. (1)(3)(4).

In 1999, TWIF received another very important boost when the sport once more received provisional Olympic recognition, which was made official in 2002. It is therefore, once again an International Olympic Committee (IOC) recognised sport, controlled under the auspices of the official governing body, the TWIF. This does not of course, mean re-entry into the Olympic Games, and that has still not happened, but it was a vital acknowledgement of the sport's respectability as a legitimate event. And with Olympic recognition came grant money to assist with the development of tug of war - vital in what has always been essentially an unfunded, amateur sport (2)(4).

The sport has come a long way. It has expanded in many other ways too with more weight divisions and age groups in competition. Indoor, as well as outdoor, events are held, and since 1986, international competition has been open to women as well as men (1). The TWIF holds World Championships every two years, with European events in the intervening years. The sport is also contested every four years at the World Games (2). Today, more than 60 nations are represented by the TWIF, literally spanning the alphabet from A-Z, from Australia to Zimbabwe, and including nations as diverse as Columbia and China, Iran and Israel, and Nepal and Nigeria (4).

Now we will take a brief detour from the history of tug of war. Shortly we will look at its status in the 21st century and the envisaged future of the sport. But first we should consider just what this sport is in the modern era - the tactics and rules of tug of war. By considering these we will show that tug of war really is a true and genuine athletic test deserving of Olympic recognition.

How To Perform Tug Of War

This video by Matty Metzger who is a Canadian representative of TWIF, has a suitably dramatic introduction as it shows competitors preparing to do battle, but most of the video consists of very clear graphics which illustrate techniques to resist, hold, and pull the opposition. It provides an effective demonstration of the various tactics and stances which are necessary to make a successful team in this sport

The Rules Of Tug Of War

Olympic representation early in the 20th century meant that international rules became necessary in the sport of tug of war, and those rules still exist today with some modifications. Strict adherence to international rules may of course be relaxed when the sport is played at a local or 'fun' level, but what follows is a simplified version of the official rules which are used in all international outdoor competitions. (Some rules do vary slightly between outdoor and indoor events).

Teams have 8 pullers, and contests are decided by the best of 2 pulls out of 3.

A hemp rope of between 10 and 12.5 cm in circumference and 33.5 to 36 m in length is used. A red tape on the rope is aligned over a mark on the ground. Also there are 2 white and 2 blue markers on the rope. The 2 white markers are 4m from the centre mark and are used to determine the result of the pull. The blue markers on the rope are 5m from the centre mark, and delineate where the front puller should grip the rope. The contest judge will issue the command:

'Pick up the rope.'

The rope is lifted. Precise rules dictate how all other pullers grip the rope, to avoid unfair advantage and to prevent injury. The rope must be gripped by both hands. It cannot be passed over the shoulder and it cannot be locked by wrapping it around the body (apart from the anchorman at the back). And then:

'Take the strain.'

The rope must then be pulled taut, and a foothold will be established by each puller, digging the foot into the ground:

'Steady.'

As soon as the rope is stationary with the centre mark level with the centre ground line, the next command is given:

'Pull.'

Both hands need to be kept on the rope at all times, so passing it through the hands is not allowed. Also, no part of the body apart from the feet is permitted to touch the ground. Minor transgressions are upbraided with a warning, and 3 warnings will lead to disqualification. A pull is won when the 4m white marker is pulled over the centre line.

Coaching is allowed.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

It must be stressed that this is just a brief summary of TWIF international rules. A comprehensive rule book can be found on the TWIF website and on the ToWA website (2)(4).

Successful Tug of War

This page is not a coaching guide, but it will help to make very clear that the sport at the highest level requires a multiplicity of disciplines, and very rigorous training to develop all of these disciplines:

Strength

The most obvious requirement is strength. Tug of war cannot be won without strength in the muscle groups of the upper body, and particularly in the legs. Various weight training routines are necessary as well as many other exercises to build up the competitors' muscle strength.

Stamina

Strength by itself is never enough. Stamina is also required, because for prolonged contests between very equally matched sides, every last gram of energy is drawn from the competitors, as can be gauged from the faces in a ToWA photo above. For much of the contest indeed there may be very little movement - just sustained holding against an equal and opposite force. It may be exhaustion, more than pure physical strength, which determines the winner and loser in a contest.

Technique

Even with great physical attributes, a powerful team can be undone by a superior technique. Best posture is with an underhand grip and the arms extended and locked. The body is leant backwards to establish a low centre of gravity. The leg muscles do most of the work, together with the upper body. When moving back, very short steps are taken, and after each step, the body may once again be anchored to prevent a counter-pull. Technique will vary between outdoor and indoor pulls. Outdoors on soft turf, feet can be dug deep into the ground. Indoors, grip on the rubber matting which is used, is more of a problem, so one cannot lean back so far, and a rhythmic pulling technique becomes even more important.

Teamwork

And in any team event, the saying goes that you're only as strong as your weakest link. Good teamwork is essential, including wise distribution of team members and coordination of movement. The lead puller takes much of the responsibility, as does the anchorman, who is the only athlete allowed to wrap the rope around his or her body. The pull should be done with the rope as straight as possible, and a good coordination of movement of all the team members is crucial to exert maximum pressure on the opposition, or alternatively maximum resistance.

Training

To achieve the necessary standard to compete internationally at tug of war, intensive training really is a necessity. Training is done several times a week, and may include weight-lifting and cycling. Running in all forms - long distance, hill climbing and sprint work - is advocated to build cardiovascular fitness, stamina and strength. One authority also suggests rope climbing to develop upper body strength. Others suggest squats, lunges and sit-ups to build up muscle. And of course rope pulls with team mates to improve technique. This advice is gleaned from several authorities, including the official ToWA website and handbook, the TWIF website, and the website of the Sandhurst Tug of War Group (2)(10)(11).

The Risk Of Injury

The rules laid out in great detail by national and international governing authorities, and summarised above, serve to give credibility to tug of war as a legitimate Olympic sport. And the training which is described above maximises the effectiveness of the competitors. But rules and good training also serve another purpose. The forces involved in top level competition when two teams are straining every muscle are so great that without physical fitness, good technique and adherence to the rules, serious injury can result.

Of course, back strain and falls are understandably a risk, but wrapping the rope around your hand or wrist (forbidden) can also lead to a very painful injury, and even amputation of fingers has occurred, especially if the wrong kind of rope is used. In 1997, two Chinese pullers had their left arms severed (later successfully re-attached in operations which lasted several hours). They had been taking part in a special festive event in Taiwan involving more than 1600 participants. The combined force involved was estimated at 80,000 kgs, but the rope they used was nylon, and it could only withstand 26,000 kgs. The rope snapped and the rebound was so severe, that it took off the men's arms.(5).

Of course, this should not put anyone off tug of war! These are exceptional cases, and provided ropes are not wrapped tightly around wrists or other body parts, tug of war is essentially a fun activity at any junior level. But the example graphically demonstrates the immense forces involved at a professional level or when massed tugs of war are conducted without proper equipment or supervision.

This video by the Tug of War Association shows the 2nd End of the Final in the 2013 National Indoor Championships Mens 680 kg event, in which Uppertown (red shirts) take on Norton (white shirts). This is a relatively short contest - frequently pulls will last for several minutes.

Sporting Values of Tug of War

Sadly in this day and age, traditional values often seem lost in the highest echelons of sports where a 'win at all costs' attitude is too readily adopted. But there surely can still be a place for decency in sport, and tug of war certainly has some values which hopefully will never be lost. During the World Games of 1989, the Swiss team were competing against Great Britain. Switzerland were one man short due to injury, so the British team voluntarily dropped one of their team in a spirit of fair play. And 20 years later, the Swiss made a similar gesture in a World Games fixture against Germany. Maybe sportsmanship is no longer such a key ingredient in the Olympics, but I'm sure everyone believes that it should be (5).

The Status of Tug of War in the 21st Century

We have seen that tug of war is a sport played throughout the world and throughout history. We have seen that tug of war is a sport with recognised international rules and competitions. And we have seen that it is a sport which demands peak physical fitness and good training techniques.

It is a true sport with a well organised club structure. There are events for men and women and for junior and under 23 categories. And as in other weight/strength related sports, many different weight divisions compete in international competition (2)(4).

However, tug of war does tend to be a sport of regional strongholds, notably in northwest Europe due to a passionate tradition which has long existed in the countries of this region. As already mentioned, the sport has also developed a following in the American Midwest. South Africa is a particularly enthusiatic tug of war nation, and across the continent of Asia, the sport is flourishing with many followers and devotees. Many other parts of the world play the sport at a low level, but may have little or no representation at the highest level, due to a lack of media exposure to increase awareness, and a lack of funding to improve standards (9).

And there are other related problems. All sports have a fun element. That needs to continue - football played in a local park, running races on a school sports day, and basketball played with friends using a net in the backyard. But sadly tug of war is too much identified with the image of fun. The public image is that of an amateur game, with children having a laugh, with village fetes or country fairs. The public do not always associate it with properly laid out rules, self-discipline and training schedules.

Finally, sports need star names to thrive in the modern era, but eight-man tug of war is not a sport which is ever likely to create celebrities. The reason is that despite fine differences in the duties of individual pullers, from the point of view of the spectator, everybody is basically doing the same job - pulling. It's not easy to identify a special player, or a team member with unique and individual skills (9).

So today tug of war is a well organised sport with a good administration and dedicated supporters, with much to recommend it as an Olympic sport. It has come a long way since 1920. It does however have issues which need to be addressed if the ultimate goal of a return to Olympic competition is to be realised. In the next two sections I will look at efforts to tackle these issues, and present a few personal thoughts on the subject.

The Future - My Own View

Here the author of this article presents his own views. I emphasise I am not a member of any tug of war club, and I have no involvement in the sport. I've written this article only because after witnessing the immense effort put into a tug of war match, I strongly believe it is a sport of true Olympian value.

1) The issue of the lack of identifiable celebrities could be addressed by having singles or doubles competitions. Is that too radical a suggestion? Any singles event would obviously lack the teamwork element but would emphasise the strength element, and the winners of Olympic singles or doubles medals could certainly achieve the star status which would greatly increase the sport's national and international profile.

2) Another suggestion could be that the conclusion to a match may be much more obvious and dramatic if instead of pulling a white marker raised high above the ground over the centre line, the match ended with the foot of the losing team's lead puller being dragged over the line.

3) As can be seen in some of these photos and videos, outdoor tug of war usually involves digging in the heels, entrenched positions, and long periods of strained pulling with little movement and churned up turf like a furrow in the mud. It does have something of a farmland look about it. Perhaps tug of war on a different surface, or indoor tug of war, would have a (literally) cleaner, more typically Olympic stadium appeal, for a worldwide audience?

However, these are only my personal suggestions, and they have no more importance than the musings of any other individual. It is for those who have dedicated their free time to this ancient sport to decide the direction in which they believe the sport should go.

Improving the International Image of Tug of War

In the previous section we touched on some of the hurdles which tug of war faces in its bid to be readmitted to the Olympic programme. So how are issues such as media exposure, lack of funding, and public image being tackled?

Unfortunately it is difficult to achieve good media exposure or funding. It is a real 'Catch 22' situation; you need good media coverage to generate international interest in the sport in the future, but why would the mass media choose to cover the sport if there is insufficient international interest today?

As for funding, advertising revenue is very hard to attract - indeed almost impossible - without media coverage. And despite all the hard work of the TWIF and other associations, and an organisation which is professional in its approach, all those involved in its administration are essentially unpaid volunteers, doing what they do for the love of the sport. That applies even to the TWIF President Cathal McKeever and executive board (9).

In spite of all these obstacles to success, McKeever and his team are trying to increase the quality of teams from all nations by introducing development courses in different parts of the world with instruction in coaching. Effort is also being focused by TWIF, and by national associations, into getting the sport back on the Olympic stage (9).

At the time of writing, 2024 is the next opportunity for it to be included in the Olympic programme. Let's hope that it is. The following section, as a conclusion to this article, sets out eight key arguments for the inclusion of Tug of War in the Olympic Games.

The Case For Olympic Representation Today

This whole article has been put together to present a case for the reintroduction of tug of war into the Olympic Games. It's time now to collate all this information into eight strong arguments in favour of its inclusion:

- Tug of war, as we have seen, has a far more ancient and far more extensive world appeal than many modern sports which have Olympic representation.

- Tug of war has far more in keeping with the Olympic motto of 'faster, higher, stronger' than many sports. And it was actually performed in ancient Greece.

- Tug of war as a team sport tests a wider range of athletic and tactical skills than some other sports - even some of the most traditional Olympic events.

- Tug of war has simple rules and objectives which make it much easier for the wider international community to understand than many more complex sports.

- Tug of war equipment at a basic level is inexpensive and accessible to all. The people of any nation, however economically disadvantaged, can take part.

- Tug of war does not require subjective scoring by a team of judges. Apart from evaluation of rule infringements, contests are clear cut and decisive.

- Tug of war has an ethos of sportsmanship which reflects traditional Olympic values - values largely lost from many of today's professional sports.

- And tug of war would benefit so much more from International representation than some elite, multi-million dollar sports included in the Olympic programme.

There are many sports which have Olympic recognition at the time of writing, which appear to have considerably less powerful arguments in their favour. Some are games without a strong traditional Olympic history, some test a narrower range of athletic abilities than tug of war, and for some of these sports, the Olympic Games is very much secondary in importance to their worldwide appeal. Whilst some may be true to the Olympic ideal, others are less so, but all have been accepted into the Olympic fold.

On the other hand, tug of war is indisputably one of the purest of all events in terms of the natural qualities and abilities it tests. And as we have seen, the case in support of tug of war on all other counts is very strong, and much stronger than that of many other sports. The message of this article is therefore very clear:

Tug of War should once again grace the Olympic stage.

This excellent video prepared by the Tug of War International Federation, tells something of the sport's history, and the dedication of all those who are involved in the sport. The video also shows tug of war exponents in action, the effort involved, and the jubilation felt when victory in a match is achieved.

Comments

Post a Comment